For the newly opened solo exhibition at NPAK, artist Rexy Tseng has created a multilayered installation ensemble that evokes global narratives while reflecting local cultural conditions. The entire exhibition serves as a crossroads between worldwide contemporaneity and the distinct Armenian “here and now.” The exhibition is open until April 5th.

Catherine Chernova, an art critic and correspondent for Lava Media, spoke with the artist about his practice, motivations, key ideas, and the role of humor in his work.

версия интервью на русском языке

Catherine Chernova: As I’ve been living here I noticed that Armenians always ask the visitors if they like the country. So, how do You like it here?

Rexy Tseng: I like it – the people are friendly, and the architecture is truly unique. It’s neither Soviet nor Turkish in style, yet I find it difficult to categorize. There’s something European about it, but it also carries influences from other regions. I like the cityscape, the architecture, and the visual culture – it feels different from anything I’ve experienced elsewhere. I found it very charming.

CC: This is your second time in Armenia, isn’t it?

RT: Yes, that’s correct. My first visit was in the summer of 2023 when I met with people at NPAK. It was my first time experiencing Yerevan in person, and everything felt fresh – a completely new experience. The summer was wonderful, and the city was romantic, especially with the street lights as I walked around the square. The city center is small and walkable – you can easily go from one end to the other.

CC: Ok. I’m very curious about the sofas in the exhibition, they seem so post-soviet, so familiar. Did You find them here?

RT: Yes, I’ll talk about the process of creating the show. I made the installation sketches in Photoshop and sent them to the team at NPAK. They offered to help find the right materials and construct the installations. Later, they shared a website where I could find the sofas.

CC: List.am?

RT: Correct. I looked through the website and selected the two pieces I liked most. Working this way is good because the materials have local characteristics rather than being generic items shipped from IKEA. When sourced locally, objects carry their own unique character – sometimes in unexpected ways, especially for someone like me, a foreigner unfamiliar with what can be found. This approach allows us to discover objects with more personality, patina, and a deeper connection to the local community. When people visit the show, they recognize the style and immediately feel a sense of connection.

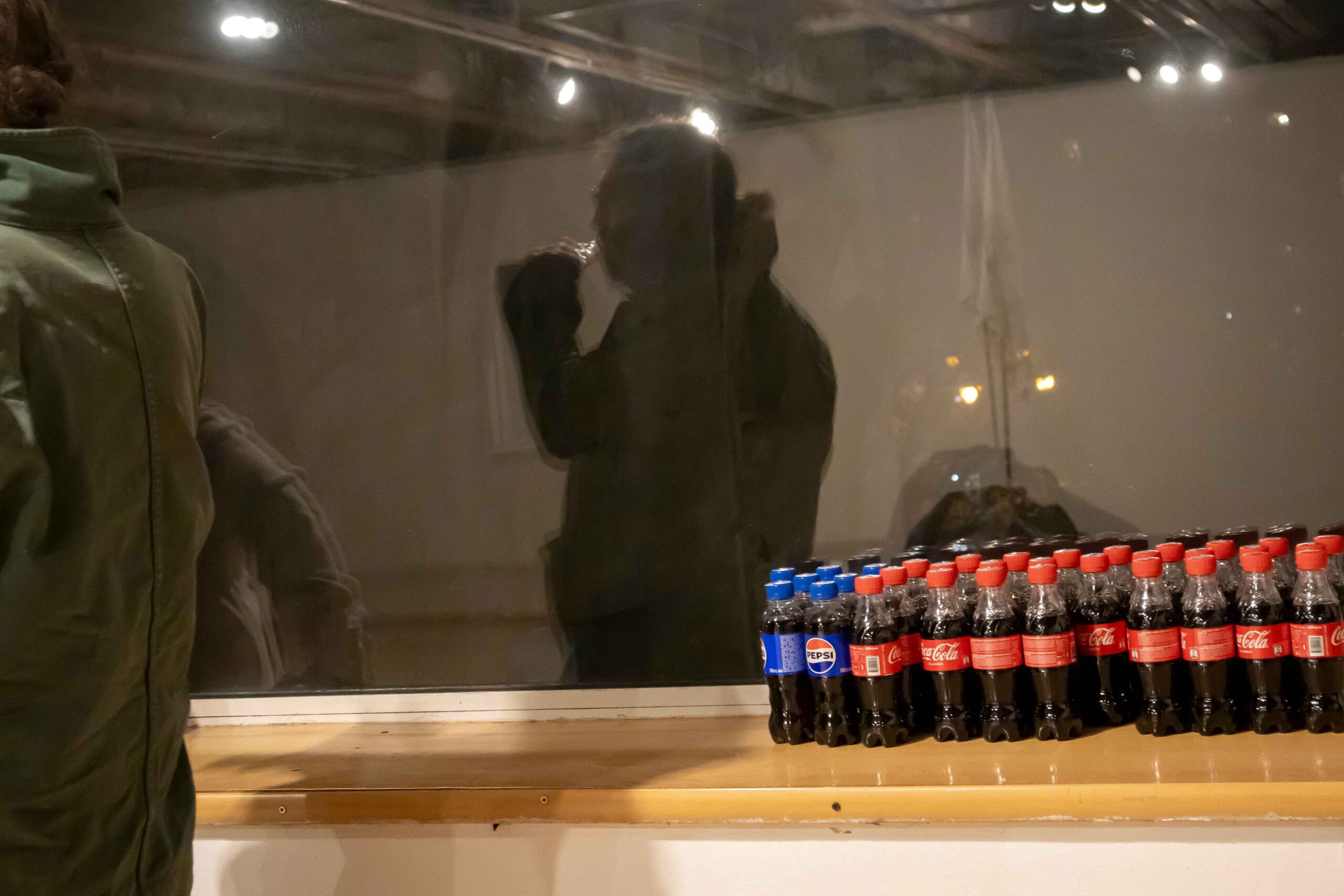

CC: I found it very interesting that there were bottles of Coca-Cola offered to the visitors at the opening night. Is it kinda participatory element?

RT: Something like this. It’s interesting because the installation with the split sofas and Coca-Cola and Pepsi bottles, reinforces its statement on consumer culture.

Photo by Davyd Mirzoyan

Photo by Davyd Mirzoyan

CC: So the visitor is a consumer of art?

RT: Well, visitors are consumers of culture, and Coca-Cola is a cultural symbol – an American product. It also represents American export and, by extension, political influence. Coca-Cola has long been associated with democracy; when it first appeared in China, it was symbolic – China was opening up to the West.

The sofa is known as a place for intimate conversations. By splitting it in half, the installation highlights a conflict of interest. Scattered throughout the sofas are Coca-Cola and Pepsi bottles – symbols of consumer culture. Despite differing opinions and power dynamics, one constant remains across this division: the shared drive to consume – an embodiment of American consumerism.

CC: American lifestyle?

RT: Yes, it’s everywhere. Whether in a post-Soviet country or Western Europe, American materialism is universal. What’s interesting is that Coke and Pepsi are supposedly competitors, right? You’re given two options – Coke or Pepsi. But when you think about it, both are American brands. No matter which one you choose, you’re ultimately buying into American capitalism. That’s the common thing throughout the entire installation.

CC: To me, honestly, Coke and Pepsi even taste the same.

RT: Almost. But both brands have a history of symbolizing American freedom – the freedom to choose and the freedom to consume. I remember a story: one of the Soviet leaders loved Pepsi so much that he bought a massive supply using warships. He literally exchanged Soviet weapons for Pepsi.

CC: Wow!

RT: Like, “I can’t give you cash, but I can exchange it with weapons”. So at one point, Pepsi was the biggest arms holder in the world because of this exchange.

When people in China or the USSR suddenly gained access to Cola, it marked a significant cultural shift. American ‘sugar water’ carries a cultural and political influence that we consume daily – often without even realizing it. That’s why the installation is titled “Lowest Common Denominator.”

Photo by Davyd Mirzoyan

Photo by Davyd Mirzoyan

CC: Ok. Moving forward, I would like to talk about Your artistic practice in general. It seems to me that, You juxtapose the big contemporary conditions, global narratives with the cultural differences. I see this juxtaposition in many of Your projects.

RT: Yeah, it happens. But it’s part of working internationally. When I first visited Armenia in 2023, I knew nothing about the country, which made creating a show challenging. But this wasn’t the first time – I often travel to different countries to create artworks and face similar challenges. I don’t always understand the local culture, I’m unfamiliar with the history, and sometimes, I don’t even know exactly where the place is – like Yerevan, which I hadn’t known much about before arriving.

There’s a general framework to my work: once I arrive, I find materials locally, research the history, and then bring everything together. But at the same time, it’s not about my interpretation of the culture – I don’t pretend to know it deeply. Instead, it’s just enough to create a sense of local connection for the audience.

CC: So, You’ve been to many countries, and it’s an important feature of Your artistic method? Like difference is the core thing in this experience of meeting another culture.

RT: Right.

CC: And it relates to the borders, the current exhibition’s concept, the problem of trying to understand people without being able to fully enter their perspective.

RT: I think it’s partly shaped by my personal experience. I was born in Taiwan and later educated in America, navigating two positions of power. In the 1980s and 1990s, Taiwan served as a manufacturing hub for the U.S. – back when everything from plastics to electronics was labeled “Made in Taiwan,” before China took over.

I moved to the U.S. when I was 13, and my position within the power dynamic shifted. I went from being part of the ‘factory’ to the other side – the consumer, where people were buying what was being made in Taiwan. My worldview changed; it became American, shaped by its cultural exports and its narrative of how the world functions. Taiwan was manufacturing goods for the U.S., which were then exported globally – but under American brands. This showed a division of power, labor, and capital: America was the boss, and Taiwan was just the worker.

Having lived on both sides, I recognize a pattern – one that continues today. America still sees itself as the center of the universe. My education as an artist was in the U.S., where cultural making is deeply tied to its own narrative. I took that perspective with me, but as I travel to different places, I encounter ideological conflicts that challenge what I’ve been taught. It’s a constant process of questioning the American-centric worldview and its influence on the art narrative

CC: American language of art?

RT: Right, everything revolves around it. One thing I found fascinating was that when I studied art history in the U.S., Russian art was completely skipped – it simply wasn’t there. Then, when I visited St. Petersburg and Moscow, I discovered incredible artists I had never heard of. They were entirely absent from the American version of art history.

CC: That’s interesting because many Russian artists create original work, but they also try to replicate what Americans have done.

RT: Well, is it really American, or is it European?

CC: It depends…

Photo by Davyd Mirzoyan

Photo by Davyd Mirzoyan

RT: See, that’s an even stranger question. Many postwar art superstars are associated with America, yet they weren’t originally American. Take Willem de Kooning, for example—he was Dutch, from Rotterdam. Or Mark Rothko – he was born in Latvia before moving to New York.

CC: But all the contemporary art is, somehow, American.

RT: Contemporary art is an American invention.

CC: And artists who explore postcolonial themes and cultural identity often come from Africa or Asia, but they all work in New York.

RT: They do.

CC: It’s great because the New York art scene is open and full of opportunities, but it still seems strange.

RT: Right, but it doesn’t represent the entire world, does it? People create art everywhere – Yerevan, Moscow, Shanghai, Beijing – and their work is just as valid. Yet the dominant narrative of ‘Western contemporary art’ remains American-centric, and that’s the situation we face today.

Much of my practice – traveling and creating art in different places – is a challenge to understand perspectives beyond the bubble I grew up in, beyond what is familiar. Is that really the only narrative? That question drives my motivation for traveling and making these projects.

CC: I think that’s a very strong motivation. And the process provides You with unexpected circumstances? Like you “meet” them?

RT: Yes, I ‘meet’ them. There are limitations, circumstances, and elements of luck – both good and bad. You have to work with all of it, and that, too, is part of the artistic practice. Ultimately, it’s about meeting the circumstances.

CC: Ok. I have a very general question about the art discourse. It often feels like a sealed, hermetically closed system – difficult to understand. Many people exist outside of it. Do you try to reach them?

RT: I think contemporary art, to some extent, is built on exclusivity. It functions like an exclusive club – accessible only to a select few who have had the privilege of education, whether through family or luck. Compared to popular culture, it operates within a much smaller and more insular circle.

CC: Even than classical art, like realistic painting.

RT: Even classical art now feels more accessible than contemporary art. But do I try to bring more people into contemporary art? No, I don’t. Some artists want to engage audiences across different social classes, ages, and educational backgrounds, trying to make art as inclusive as possible. I’m not very good at making accessible works. However, I believe that even without understanding the theory or political history behind a work, there’s still a visceral response to the material – you recognize it on some level. Even without full comprehension, there’s still room for enjoyment.

Photo by Davyd Mirzoyan

CC: Tell me about this figure wrapped with tape.

RT: This packaging idea started with a meme I found – someone at an airport was shipping a lamp that looked like a human. I thought, “Wow, this is so absurd!” That viral internet video inspired me to create an installation about empty airports during COVID. For me, it was the perfect symbol of that time – when people were separated yet deeply wanted to reunite. It was also a period when people were literally living off Amazon orders. Packages became a lifeline, holding society together. But when you really think about it, it’s absurd. It’s something we take for granted now, but when Amazon first started, people didn’t even trust the website, unsure whether their package would actually arrive in two weeks.

I see this as the ideal example of techno-capitalism – a fusion of the internet, delivery technology, and commerce. These elements have seamlessly intertwined to form the fabric of today’s society, with packaging now dominating our daily lives. We’ve become deeply attached to internet shopping.

CC: About the funny things. You use dark humour in Your practice. Can You explain what it means to You as an artist?

RT: I think dark humor isn’t always obvious. When you first see the human figure, it appears grotesque, right? It could be a dead body, or it could be something else entirely. If you don’t know what’s inside, there’s a sense of mystery, yet at the same time, it’s harmless. And when you stand in front of it, it looks almost pathetic. This triggers different layers of interpretation. That’s where the dark humor happens – it’s absurd, yet it can also be seen as funny. In a way, this duality is key to understanding contemporary art.

CC: So it’s a multilayered massage?

RT: Definitely. I see dark humor as a key component of contemporary art. It offers a way to see the world not simply as black and white. It’s this gray mixture. At first, it may seem pessimistic, but beneath the surface, there’s an underlying sense of optimism.

If you accept things that happen in life as absurd situations, then you can laugh it off and say “Yeah, sure”. We just go on, you know.

Photo by Kate Chernova

Catherine Chernova

версия интервью на русском языке